Archives: Anchors For Attention

“The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries.” ― Jorge Luis Borges, The Library of Babel

Welcome to The Flâneurs Project. In this post, I look into the allure of archives and how they can anchor our attention.

Speaking of archives, I’ve compiled all the interviews I’ve conducted so far with friends and readers into a dedicated page on Substack. This page will be regularly updated and maintained. While the interviews page is quite extensive, it is easy to navigate—just click on the left-hand menu to select a title or question that piques your curiosity.

Infinite Archives

I think we are all collectors of some kind, tending to our (infinite) archives every single day—both online (Substacks, social media timelines) and physical (memorabilia, libraries, and more).

There’s something profoundly alluring about infinite archives. I dare to say that every collection is an infinite archive—not merely a gathering of objects, but a vast web of relationships. A collection is more than the sum of its parts; it is shaped by the countless ways those parts relate to one another, to every observer who encounters and engages with them, and to the myriad possibilities for mapping, displaying, or reinterpreting the collection.

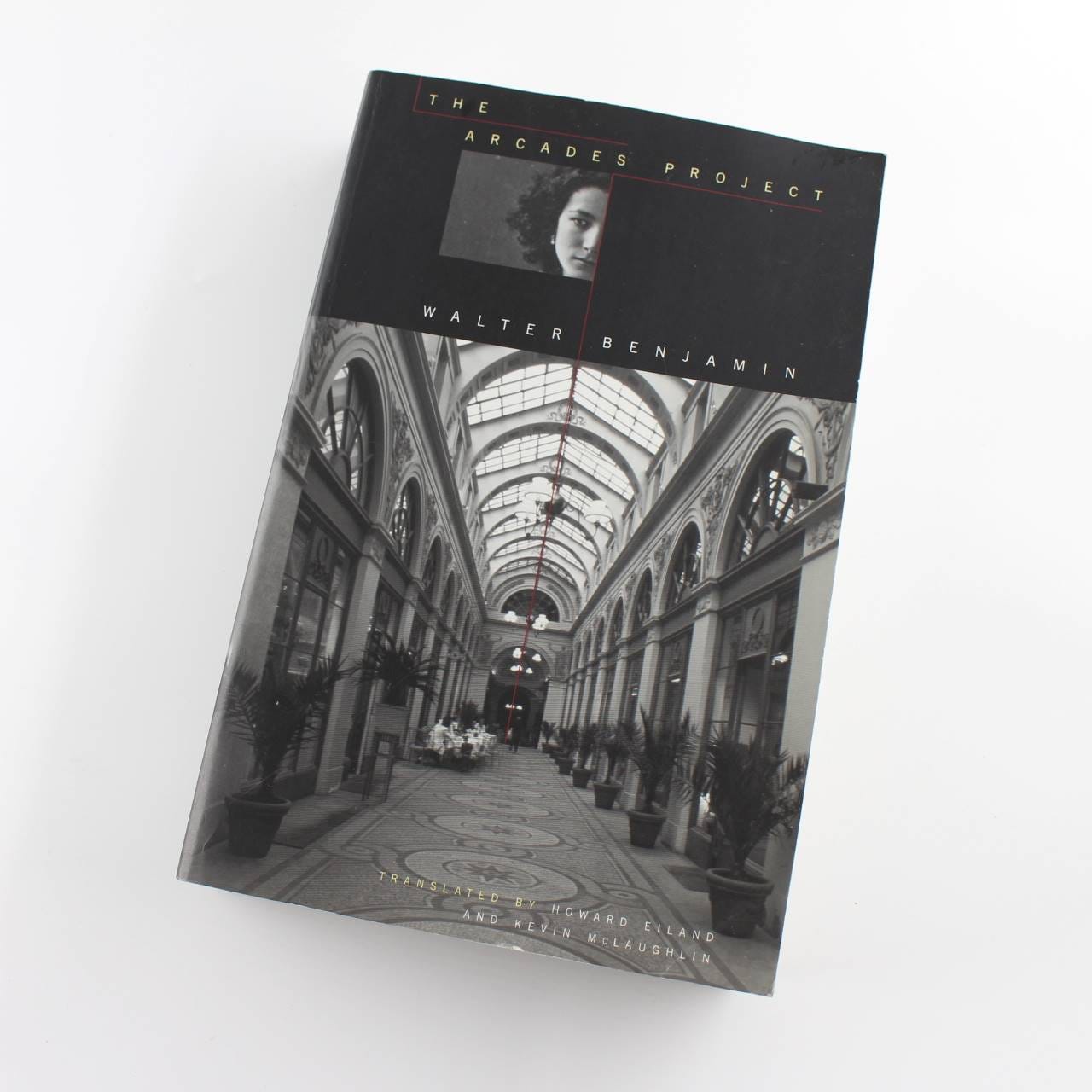

A book that epitomizes the concept of the infinite archive is Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project, an unfinished thousand-page montage of quotes, references, essays, and fragmented notes. While ostensibly about the Parisian arcades, it is so much more: a critique of his era, a snapshot of history, and an ambitious attempt to transcend the fallibility of memory through meticulous documentation.

I don’t think I would be as passionate about archives and collections if it weren’t for Walter Benjamin’s work. He seamlessly merged the roles of archivist and collector, reshaping our understanding of memory, knowledge, and history.

Benjamin was not only a writer and philosopher but also a true collector—one whose passion transcended personal obsession to reflect the Zeitgeist, the spirit of his time. Among his most cherished collections was his library, which he described lovingly in his essay Unpacking My Library:

“For inside him there are spirits, or at least little genii, which have seen to it that for a collector—and I mean a real collector, a collector as he ought to be—ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects.

Not that they come alive in him; it is he who lives in them.”

The book Walter Benjamin’s Archive beautifully unveils and describes Benjamin’s different archives, emphasizing the passion and intense curiosity that drove him—beyond methodology, beyond rules.

“Order, efficiency, completeness, and objectivity are the principles of archival work. In contrast to this, Benjamin’s archives reveal the passions of the collector.”

“Benjamin’s archives consist of images, texts, signs, things that one can see and touch, but they are also a reservoir of experiences, ideas, and hopes, all of which have been inventoried and analyzed by their stock taker.”

Benjamin was also an avid picture postcard collector, finding meaning in the act of constantly revisiting them. For him, collecting was “a form of practical memory,” a way to preserve and engage with fragments of the past.

“There are people who think they find the key to their destinies in heredity, others in horoscopes, others again in education. For my part, I believe that I would gain numerous insights into my later life from my collection of picture postcards, if I were to leaf through it again today.”

Walter Benjamin

Memory, Amnesia, and Long-Durée

Another collector who has deeply inspired my work and fueled my obsession with archives is the Swiss curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. He is renowned for the various archives he tends to every day. One of them is an ongoing library housed in an apartment in Berlin, which he purchased solely to store his books—an extension of his daily ritual of buying one book per day.

Another archive he curates is his collection of ongoing interviews with artists, writers, architects, scientists, and more. He has conducted over 4,000 interviews to date, many of which have been published in various books. During the pandemic, he conducted 2-3 interviews per day via Zoom, reaching out to artists, scientists, creatives all around the world.

Obrist is also a promoter of long-durée forms—lifelong projects nurtured with care, which he describes as a “protest against forgetting.” These projects reflect his dedication to preserving memory and resisting the erosion of time, the “amnesia” of today, offering a counterpoint to the fleeting nature of modern culture.

THE WHITE REVIEW

— “You’ve said previously that ‘memory is very radical right now’ – could you expand upon that?”

HANS ULRICH OBRIST

— “I suppose it has to do with something Rem Koolhaas once said. He thinks information doesn’t necessarily produce memory, that maybe amnesia is widespread in the digital age. It also arose from a conversation I had with Rosemarie Trockel, who said that I should go and interview really old people, those who have seen the most. Since that conversation I’ve visited thirty-eight people who are either centenarians or in their mid-to-late nineties, including Albert Hoffman and Nathalie Sarraute, someone who has been too widely forgotten.

The more of these interviews I did, the more I realised that these people don’t have so much presence online, which is equivalent now to a kind of collective amnesia. The interview project, like curating, is a way of working on memory, a protest against forgetting.”

Archives As Anchors

Collecting and archiving are ways to reclaim and own our attention—they are acts of meaning-making. These practices are rituals: habits and skills that demand time, patience, and a willingness to look beyond the surface.

To collect well is to resist algorithmic influence. A true collection reflects deeply personal values and a genuine desire to know, understand, and reveal.

Collecting and archiving ground us. They invite us to trace connections, dismantle rigid categorizations, and uncover links between the unexpected.

Whenever I slip into collector-archivist mode online—chasing rabbit holes of papers, forgotten PDFs, or obscure books—I break free from the pull of mindless consumption. I am no longer swept away by the endless timelines shouting, “This is important! This is important!” Instead, I resist the lure of aimless scrolling and embrace a slower, more deliberate way of engaging with the information I encounter.

Attention and deep awareness, after all, are the collector’s most precious assets.

Thank you for reading. As always, I welcome your notes, emails, and stories.

– Patricia-Andra Hurducaș