The Melbourne Flâneur

The Frenchness of Australian life, the spleen of Melbourne, the ‘Noir Place,’ and the search for the ‘New Life’: An interview with writer Dean Kyte.

Welcome to The Flâneurs Project. In this interview, Australian writer and filmmaker Dean Kyte answers a few questions about his creative projects, his favourite places to write in Melbourne, Bellingen, and Paris, and how he became the Melbourne Flâneur.

‘[a]u fond de l’Inconnu pour trouver du nouveau!’—‘[t]o the depths of the Unknown to find… something new!’ - Charles Baudelaire

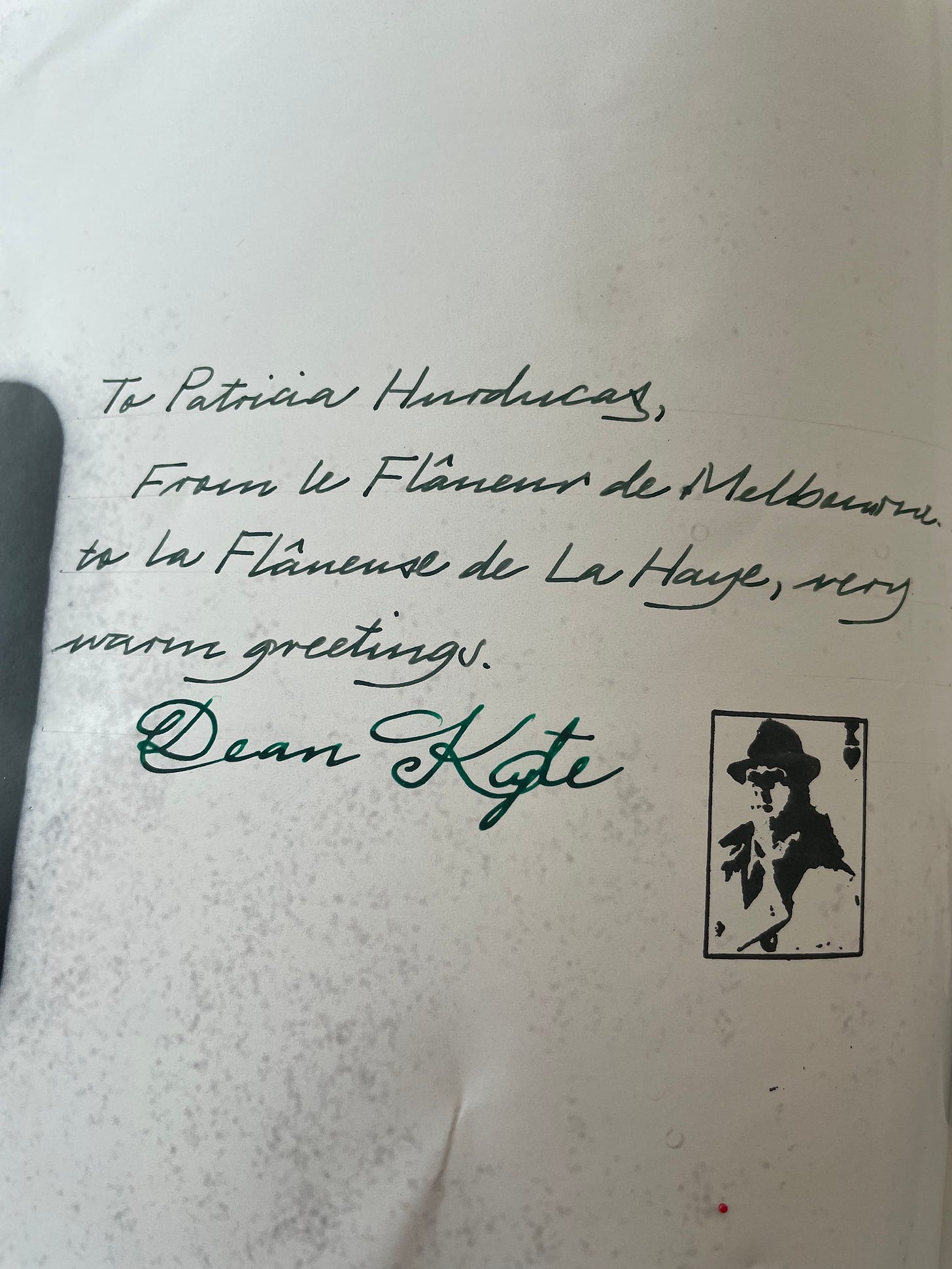

I’ve never visited Australia, but after my brief conversation with Dean and receiving the Melbourne Flâneur zine I ordered by post, I know for sure that Melbourne is on my list of places to visit in the coming years.

I met Dean Kyte while cyberflâneuring on Airchat. If I remember correctly, he left me a voice note mentioning that he remembered my name because he stumbled upon an essay of mine years ago, back when I was still writing somewhat obscurely on WordPress. Curious, I googled his work and was immediately captivated by the attention to detail and the dedication he pours into his creations—his writing, his videos, his photography, and his presence as “the Melbourne flâneur.”

When my order arrived, having travelled from Australia to The Netherlands in just a few weeks, I was thrilled. I took my time unpacking everything: the zine, the postcard, the letter, and the CD, all carefully wrapped by Dean in a map of the Melbourne tram network.

The entire unpacking experience filled me with a deep sense of connection and joy. It made me slow down and savour every detail—the handwritten letter, the black-and-white photographs, and the palpable care, time, and attention that went into every aspect of it.

“Writing is a true ‘manual labour’. But, as Ulmer observes, it is also a labour of time and of being, in which we don’t just ‘do’ writing but live writing. To be a writer is to live an artisanal lifestyle,” writes Dean in A ‘Slow’ Approach to Offering Value.

There are people who write, and then there are those who truly embody what they write about. I believe Dean belongs to the latter.

Below, I’m sharing Dean’s answers to some questions I sent him via email a few weeks ago. This interview is longer than those I usually share here, and it’s meant to be enjoyed slowly—bit by bit, with long pauses, allowing yourself to return and linger.

Hi Dean! Please tell us a little about yourself and your creative projects.

My name’s Dean Kyte. I’m a Melbourne-based writer, filmmaker, and flâneur. I craft fine literature: I translate the poetry and prose poems of Charles Baudelaire from French and I also write my own prose poetry, capsule essays and literary fiction based on my flâneries in the towns and cities of Australia. I release the pieces as short videos on Vimeo and as audio tracks on Bandcamp.

My major creative project is The Spleen of Melbourne, which is a collection of prose poems and literary crime ficciones based on scenes of contemporary Melbourne life. I released the first version of The Spleen of Melbourne project as a CD of spoken word tracks accompanied by atmospheric soundscapes at the beginning of 2022, and last year I released the most popular track on the album, a short story called “Office at night”, as a CD single. Both the album and the single are illustrated by my analogue street photography of Melbourne, which often inspires my writing.

The next iteration of The Spleen of Melbourne project will be a Blu-ray Disc of 25 short films and videos which will enable viewers to take random, thematic flâneries through a virtual Melbourne. Eventually I plan to release The Spleen of Melbourne as a book featuring 50 prose poems illustrated by my photography, and with some kind of augmented, immersive capability that allows people to not only read the prose poems, but to listen to them as digital audio tracks or to watch them as ‘cinepoems’.

I’m also currently writing and producing episodes of a specifically fictional sub-project of The Spleen of Melbourne, a long-form audio narrative. The “Office at night” single is an experimental preview for that podcast. Whereas The Spleen of Melbourne is influenced by the French prose poems of Charles Baudelaire collected in Le Spleen de Paris, “Office at night” and other ficciones for the forthcoming podcast are written in a style I call the ‘nouvelle démeublée noire’—the ‘unfurnished dark short story’—which I’ve developed based on the principles of the French Nouveau Roman set forth by Alain Robbe-Grillet.

When did you first come across the concept of the “flâneur”?

I’m not sure. I believe I had some vague sense of the notion of flânerie when I was living on the Gold Coast in my early twenties. The conceptual relationship between writing, pedestrianism, and the rare and random experience of fugitive beauty in the urban environment which makes life almost bearable under conditions of technological, capitalistic modernity formed a nexus of concerns that my thoughts were continually circling around in those years.

Between 2004 and 2007, I wrote film criticism for magazines on the Gold Coast, and I called my journeys by foot and public transport to various cinemas on the Gold Coast and in Brisbane ‘adventures’. The experience of the movie was part of a continuum of altered experience which encompassed the journey to and from the cinema—the whole substance of the day, in fact.

Every marvellous moment on those rare days of my life seemed connected in the fine, diffuse fabric of an altered state. I wanted to live whole days of my life in such a state—a permanent floating world of Keatsian Truth and Beauty.

Through the apprenticeship of film criticism, I began to develop an æsthetic lifestyle philosophy, and one day late in 2008, I decided to learn French and go and live in Paris.

I spent the summer of 2009 living there, and I would certainly have known what flânerie was by that time. I believe that, through my new-found access to and slowly growing competence in the French language, what I had previously called ‘adventures’, I progressively began to more properly call ‘flâneries’, but I’m not sure.

As best as I can make out, the first time that the word ‘flâneur’ appears in any of my published writings is in an article I wrote on the work of the Belgian photographer Rémy Rusotto (@slab_remyrussotto on Instagram) in January 2012. In that article, I described Rémy as having a Baudelairean ‘flâneur æsthetic’.

The concept of flânerie is also mentioned six times in my first book, Orpheid: L’Arrivée, which I published in December of that year. Orpheid: L’Arrivée was based on my experiences as a flâneur in Paris, so I had clearly acquired an understanding of the concept sometime during the three years or so it took me to write the book.

What I now call my æsthetic lifestyle philosophy of flânerie has undergone two ‘crystallizations’, two solidifications and refinements since.

The first occurred in 2016. Halfway through that year, I left the small country town of Bellingen, on the North Coast of New South Wales, where I had been living, to come to Melbourne for the first time. Melbourne is the most European city on Australian soil, and when I decided to permanently settle there towards the end of 2016, the idea for The Spleen of Melbourne project began to form in my mind.

Then, in 2019-20, when I launched The Melbourne Flâneur vlog and The Spleen of Melbourne project began to firmly come together in my mind, the æsthetic philosophy of flânerie underwent a further solidification and refinement until now the lifestyle philosophy I’ve developed over the last twenty years contains well over 350 ideas and sources that I regularly draw on in my prose poetry, fiction, and critical writings.

What drives you to create—whether it’s writing, filming, or taking photographs?

I’m driven to create poetry in words and images out of the banal prose of everyday life by the same things that drove the first philosopher of flânerie, Charles Baudelaire, to write poetry—what he calls, in the first section of Les Fleurs du mal, the twin poles of ‘Spleen et Idéal’.

In Modernity, we are torn between these poles of Baudelairean Spleen (which I define in The Spleen of Melbourne as a ‘sinister tristesse’, a combination of ‘bilious melancholy’ and ‘choleric sorrow’) and the desire for ‘the Ideal’—a floating world and an eternal life of Truth and Beauty. ‘Modernity’ is a dark conceptual complex composed of what I call the ‘Satanic Trinity’ of Science, Technology, and Capital. These things, Blake’s ‘dark, Satanic Mills’, promise us the Ideal but deliver us only Spleen—a discontented ennui with modern life.

Despite all the progress brought about by the wonders of Science (Baudelaire’s Satan Trismegistus) and its two handmaidens, Technology in the material sphere and Capital in the social, the dandy-flâneur experiences a ‘dark enlightenment’ where he realizes that life within this Foucauldian grille, the ‘carceral liberty’ of the Lawrentian ‘Machine’ of Modernity, is not really worth living.

Thus, as I conceive him (and as I conceive myself as a Parisian flâneur exiled in Melbourne), the dandy-flâneur is an ‘æsthetic terrorist’ to the bourgeois order, a man who goes out into the public square and blows up his own life daily in a vision of Truth and Beauty where he himself is the chef d’œuvre, the Magnum Opus and the Lapis Philosophorum—the elegant end of his own Art, the anonymous yet spectacular cynosure of all passing eyes in the street.

The dandy-flâneur is Poe’s ‘Man of the Crowd’—he is ‘the type and genius of deep crime’. In his incarnation as an homme de lettres, the dandy-flâneur is the most intransigent résistant to the technological, capitalistic Machine of a Modernity in exponential, existential decline: he is an undercover spy ‘sousveilling’ it; he is a saboteur covertly undermining it from within by his Non serviam.

The peak of Modernity was World War II; that was when Faustian logic of Western civilization arrived at its ‘Final Solution’: the totalizing enslavement and extermination of humanity by the Machine. So, like Baudelaire before me, I am driven to create poetry in words and images out of the banal prose of everyday life, to assert my unsubmitting humanity against the Machine as an act of underground resistance, as an act of ‘æsthetic terror’ against the invidious, bourgeois interests of scientistic, technological capital.

Man cannot live by bread alone, and the dry bread of Science, Technology and Capital do not really nourish the human soul, even though they make our material lives progressively easier and more comfortable. Faced with the jail of this progressive liberty, the dandy-flâneur, as Baudelaire shows us in Les Fleurs du mal and Le Spleen de Paris, wanders the streets of the modern megalopolis that is Paris in search of an ever-renewing novelty—what Guy Debord called ‘the Spectacle’.

And the psychological rent, the cognitive dissonance between the Spleen of life that the ‘marvellous’ Spectacle of Modernity engenders and the sublime spiritual Ideal that we actually desire drives the ‘positively maladjusted’, non-conforming dandy-flâneur towards the spiritual suicide of a salutary madness: At the end of Les Fleurs du mal, Baudelaire literally cries out to Death, the ‘old captain’, to execute him with its poison, to lift up the anchor and cast out, in this endless quest for heightened, novel experience, on the final possible flânerie ‘[a]u fond de l’Inconnu pour trouver du nouveau!’—‘[t]o the depths of the Unknown to find… something new!’

So, that’s why I have been driven these past twenty years to work out the hyperobjective ‘problem of Modernity’ in the three dimensions of my flâneurial prose poetry, fiction, and critical writings: I am seeking a Dantean ‘Vita Nuova’—a ‘New Life’ for myself. What drives me to create is that quest for ‘something new’. Flânerie is a means of æsthetic investigation of the dark, pathological complex of Modernity. It’s also a set of guerrilla strategies of resistance to it. And it’s an æsthetic means of finding solutions to the ‘Final Solution’ of Faustian Modernity.

As far as I am aware, the only two writers before myself who have truly understood the æsthetic philosophy of flânerie and have made it the basis of their whole existences are Charles Baudelaire in the nineteenth century and Walter Benjamin in the twentieth. Baudelaire identifies more with the conceptual figure of the dandy, Benjamin more with the conceptual figure of the flâneur, and in my work, I have sought to reconcile the two into a single conceptual figure, the dandy-flâneur, which I embody as the prism for investigating the hyperobjective problem of Modernity.

I see myself as being in a direct line of intellectual descent from those two gentlemen. All three of us are prophets of our centuries: In the nineteenth century, at the very start of Modernity, Baudelaire predicted the exponential decline of the myth of linear, technological Progress we are now experiencing. In the twentieth century, Benjamin, as a German Jew at the height of Modernity, was forced to commit suicide—by poison—precisely to avoid the Final Solution of being enslaved and exterminated by the Machine. And in the twenty-first century, I stumble around postmodern Melbourne as a Parisian in exile, a ‘refugee from Modernity’ amid the ruins and rubble of a dark conceptual complex, the hyperobject of Modernity, which is coming down around us at an exponential rate.

So, it’s been given to a Frenchman, a German Jew, and an Australian from the New World to embody the beginning of modern decadence, the peak of it as symbolic scapegoat, and the new man who might potentially emerge from the rubble of postmodern decline.

As a writer who has mapped out a considerable corner of the hyperobjective problem of Modernity through my æsthetic philosophy of flânerie, I have a profound sense that if I can solve the problem for myself of ‘how to live’ under the oppressive conditions of a Machine that does not simply want to grind our bones to dust but own our souls as well, without giving in to it, then I will also be solving the problem for a great many other artistic ‘refugees from Modernity’ who are also seeking an alternative lifestyle to a globalized Western civilization which is now in exponential, existential decline.

What is the most rewarding part of your work?

The reward is yet to come.

Like Baudelaire, I focus on the noir side of life, on spleen and ennui, on the fundamental dissatisfaction I feel with the big con of a modern life I have never bought into because I do not believe that we are anywhere close to hitting rock-bottom in the decline of our globalized Western civilization. Before we can get past this to a New Life, we must face the externalities of the old one honestly; we must address the darkness in ourselves.

To feel Baudelairean Spleen, to really feel this ‘sinister tristesse’, this ‘bilious melancholy’ and ‘choleric sorrow’ I invoke in The Spleen of Melbourne, is to honestly mourn the deception—and la déception—that lies at the heart of the modern myth of Progress. It’s to go through the stages of grief for our dying civilization.

Most people are still at the stage of denial. Our bureaucratic and technocratic overlords, who earnestly believe that they are running the Machine, are at the equally delusive stage of bargaining with it. I’m at the stage of depression, and I’m determined, like Baudelaire, to go to the blackest depths of my despair and grief about a modern life I never even believed in so as to find the light of something new.

The reward for me will be to see and experience the hopeful green shoots of a new, networkcentric culture. That’s the ‘New Life’ I am seeking to pioneer for myself and to share with others—if my strategies of resistance prove ultimately to be successful rather than quixotic.

To be a writer, an homme de lettres, in the increasingly oral twenty-first century is to be a truly quixotic figure for whom the dark, Satanic Mills of Modernity have no need. I am actually an impediment to the Machine, a stumblingblock grinding its gears—the foundation stone for a qualitatively new order of life that the bureaucratic and technocratic builders have rejected as possessing no quantifiable value.

In his capacity as Poe’s ‘Man of the Crowd’, the dandy-flâneur is a prophetic figure of the future who is pushed, by his society, to the absolute margins of it in the present. And yet, he is nevertheless at its secret centre, a ‘célébrité anonyme’ overlooked by the panoptic forces of techno-bureaucratic capitalism but laterally recognized by other edges in the peer-to-peer network who ‘grok his vibe’.

So, having to labour undercover against the oppressive sensemaking régime of a corrupted Science, and the corrupt Technology and Capital that are derived from it, the most practically rewarding thing for me is to sell my work in a parallel economy, to gain underground readers, viewers, and auditors of my ideas, and to be able to go on resisting and not submitting to the final, inhuman—and anti-human—logic of the Machine.

As a ‘poet in prose’, I am not a ‘mainstream, bestselling author’ but necessarily a ‘côterie poet’. As such, I require ‘the côterie’—the parallel social network of the literary salon, the exclusive group of readers who are as avant-garde in their taste as I am in my style, people who ‘get me’, who appreciate my effort to resist the Machine, and who support that quixotic gesture. It means a very great deal to me to discover receptive and supportive edges in this parallel network and I try to cultivate generative relationships with these people. That is where I find my greatest reward.

Which parts of Melbourne speak to you the most?

It’s difficult to say. I have a much wider experience of Melbourne than most Melburnians because I thoroughly live out my values as a dandy-flâneur: I am truly a refugee. I live out of a suitcase, and in any given month I can be living in several of the most disparate suburbs.

That said, when it came time to choose a location where the protagonist of the forthcoming podcast would live, I chose a particular neighbourhood in Fitzroy North, in the City of Yarra, as the principal locale for the narrative.

Fitzroy was the first suburb of Melbourne, established in 1839, four years after the city’s founding. The inner-city suburb of Fitzroy is well-known in Australia for being very ‘alternative’ and ‘artistic’, and the whole of the City of Yarra, which adjoins the City of Melbourne on its eastern boundary, is very ‘bourgeois-bohemian’ and extremely left-leaning in its politics. This makes it a rather odd place for the protagonist of the serial to reside: As the character in the forthcoming podcast who is most like myself, who is, in fact, my ‘Golden Shadow’, the idealization of my dark side, this dandistic ‘Man of the Crowd’ who casts out on his daily peregrinations around Melbourne from a certain terrace-house in a certain street in Fitzroy North is certainly not sympathetic to the political persuasion of his neighbours.

I’ve often ruminated in my wanderings around Fitzroy and other parts of Melbourne that lean progressive how I came to situate him there in Yarra, and I can only conclude that, in these élitist enclaves which are most aligned to the pathologies of Modernity, which are most partisanly on the side of technocracy, bureaucracy, academia, media, and surveillance capitalism, a fashionable figure who most resembles ‘the type of person who ought to live in Fitzroy’ finds his greatest liberty as a résistant to the established order right in the carceral heart of the Spectacle.

Are there any cafés, restaurants that you visit often?

I acquired the habit of writing in cafés in Paris. In the evenings, I used to go to Le Cépage Montmartrois in the rue Caulaincourt and drink a demi of beer as I wrote in my cahier. In Orpheid: L’Arrivée, I described Le Cépage as ‘le sein d’or’—‘the golden bosom’—and that is what it will always be to me: the moment I saw it I knew that I had arrived at the place on earth which is my heart’s home. For me, it will always be the greatest café on earth, and the experience of it has coloured my experience of cafés in Australia, for I am always seeking another ‘sein d’or du Cépage’.

In the little town of Bellingen, where I lived from 2014-6, I found something approaching it: When the friends who introduced me to the town took me immediately to what was then The Vintage Nest in Hyde Street, I knew I was going to stay and live in Bello. There’s a scene in my 2016 book Follow Me, My Lovely… set in The Vintage Nest shortly before it changed hands (and changed its character) which is one of my most memorable experiences of it and, I think, one of my finest pieces of writing about the part of flâneurial life that takes place in cafés.

Almost every day for two years, I was a conspicuous figure in what then became Hyde Bellingen, being indulgently allowed by the managers to write for hours over a long black. Even now, whenever I go back to Bello, I regard the Hyde as my ‘office’ there.

I have other such ‘offices’, cafés I habitually adopt as places to write, in towns and cities all over Australia. In Melbourne, I can recommend places in many suburbs, but in the City itself, the area that most reminds me of the cafés I knew in Paris is Flinders Quarter. Degraves Street is the laneway that most reminds me of my evenings ‘au sein d’or du Cépage’, and you will not infrequently find me seated on the terrace of Café Andiamo or in the window of The Quarter, writing in the evenings. In the mornings, if I’m in the City, I’m mostly to be found on the terrace of Caffè e Torta, located at the Little Collins Street end of the Royal Arcade.

But even though Australia has acquired a Continental taste for coffee, it’s really a land of pubs. So I’ll give an honourable shout-out to my Sydney watering-hole, The Carrington Hotel (or ‘The Carro’, as Australians are wont to call it) in Surry Hills: If I’m in Sydney, you’ll often see me nursing a Guinness in the window as I write or read a French book.

In your opinion, what city in Australia is severely underrated for urban exploration?

Rather than the cities, one should try to get out into countryside to understand what Australia really has to offer in terms of an antipodean adaptation of Parisian flânerie. Distances in Australia can be vast, so this is not always practical.

Victoria (of which Melbourne is the capital) is the second smallest state in Australia and is equivalent in size to some European countries, so the distances are more manageable. A two-, three- or four-hour train trip in any direction out of Melbourne will take you to some delightful regional towns and cities.

But I cannot put the case too strongly for the little country town of Bellingen, on the New South Wales North Coast. No place on earth except Paris itself has been more significant to me in my flâneurial life and writing. It was, in fact, the place where I began to practically implement—albeit in a highly reduced and circumscribed way—the tenets of my æsthetic lifestyle philosophy based on what I had discovered and learned in Paris. Before I was ‘the Melbourne Flâneur’, I was ‘the flâneur of Bellingen’!

As soon as I arrived in Bello, and for the two years or so that I lived there, people told me I wouldn’t stay long, that I would go to Melbourne, that, in my suits and snapbrimmed hat, I ‘belonged’ down there rather than among the barefoot hippies and flannelette-clad country-folk. Though I didn’t believe them at the time, they were right.

But if I had to describe Bellingen, I would say that if you took the map of Melbourne and folded it down to just two small streets—Hyde and Church Streets—you would have Bello, the most cosmopolitan city you will find in an Australian country town.

I used to flâne in a daily circuit up one side of Hyde Street, around the war memorial, and back down the other, and I felt almost as satisfied with life as in the days when I used to flâne up the Champs-Élysées, circumambulate the Arc de Triomphe, and stroll back down the other side of the greatest street in the world. In Melbourne, a flânerie up the so-called ‘Paris End’ of Collins Street still does not fill me with quite as much joy as a flânerie up Hyde Street does.

Bellingen was colonized by hippies in the early 1970s following Australia’s answer to Woodstock, the Aquarius Festival, an alternative lifestyle festival held at Nimbin, a small town some 200 km north of Bello. As an Aquarian myself, as someone fundamentally oriented towards a better collective future for humanity through realization of the individual, it’s perhaps not a surprise that Bellingen should resonate with me. It’s the one place apart from Paris where, time and again, I have had flâneurial intimations of the networkcentric ‘New Life’ I am seeking as a flâneur. It’s the place on earth where I’ve been the most consistently happy for the longest period of my life.

Strange to say, but at night that little country town is as beautiful and romantic as la Ville Lumière. I think I demonstrate as much in Follow Me, My Lovely…, which charts an entire flânerie I took with a Norwegian tourist over the course of some nine or ten hours. That was only one of several romantic experiences and altered states of being I’ve had in Bello which have showed me, as Paris did, what life could be like if we lived in a perpetual state of Truth and Beauty.

Is there a part of Melbourne you would like to re-enchant?

The ‘enchantment’ of Melbourne lies precisely in its quality of degradation. This is a theme I return to in The Spleen of Melbourne project. In one of its dimensions, Convolute P of The Spleen of Melbourne, entitled “Petra”, is devoted to prose poems that deal with Melbourne as a site of ‘modern ruin’.

As a city rapidly built in the nineteenth century on the spoils of gold, Melbourne overtook Sydney as the principal city on the Australian continent. It maintained its financial, political and cultural primacy over Sydney well into the twentieth century. But following the Olympic Games in 1956, in a sustained campaign of what can only be described as ‘civic vandalism’, the European-style city that had been built during the ‘marvellous’ period of Melbourne’s wealth was gradually taken apart by Whelan the Wrecker, a local demolition company.

Whelan the Wrecker is the baron Haussmann of Melbourne: Just as Haussmann made Paris the world’s first modern city by vandalizing its medieval heritage, so Whelan the Wrecker made Melbourne the post-modern city it is today by gradually tearing down its modern heritage.

In less than 200 years of civic life, Melbourne has gone from being a grid of rough dirt tracks scratched on the rive droite of the Yarra River to a decadent postmodern megalopolis. If the Paris of baron Haussmann was, as Walter Benjamin contends, the ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’, then I would argue that Melbourne, rather than being the ‘seventh city of the British Empire’, was in fact ‘la fille aînée du Second Empire’ (‘the Elder Daughter of the Second Empire’). Gold was discovered in the hinterlands of Melbourne in the very year that Napoleon III was dissolving the Second Republic; the city’s rapid modernization commenced apace with the institution of the Second Empire and the modernization of Paris under Haussmann.

To this day, survivals of Second Empire-influenced architecture that have escaped Whelan’s wrecking ball can be found in Melbourne’s streets. For me, what gives the city its enchanting quality is its ‘genteel shabbiness’, the profound sense I get of tripping among modern ruins—vast lacunæ in the landscape of buildings I know to have been there once but which I cannot see, ‘holes’ that have been filled with the architectural wreckage of postmodernity. I love to stroll through suburban streets and see the paint peeling from the rows of poorly maintained terraces with their fractured urns and defaced mascarons and rusty cast-iron awnings. The street art and graffiti that interacts with the battered façades—and which is always changing—are like the layers of moss growing over the toppled columns in a painting by Lorrain.

I wouldn’t ‘re-enchant’ a part of Melbourne; for me, it is enchanting. Just as Baudelaire laments the medieval Paris falling around him to Haussmann’s hammer in “Le Cygne”, for me, it’s the sorrowful vision of what has been lost—and what has miraculously survived—that makes Melbourne surreally ‘marvellous’ and enchanting.

If you could name a street, what name would you choose?

I mentioned the neighbourhood in Fitzroy North which forms the principal location for the forthcoming audio narrative. I have actually renamed one of the streets at the intersection where my protagonist’s apartment is located in the podcast, substituting the surname of one of the original Fitzroy City councillors of 1858 for another who does not have a street to his credit.

But in real life, I think that, if I were to name a street, I would have to have a specific street in mind, and I cannot think of a street in my flâneurial experience whose name I would want to change. That seems too grave a responsibility. The names of streets have a particular incantatory power for me, in life as in my writing. The naming of specific streets in my flâneurial experience, the precise description of them, and the fact that readers can theoretically navigate their own flâneries, street-by-street, from the names and descriptions I provide are distinguishing qualities of my flâneurial literary style.

I have such a vast experience of streets in this country! I travel so far and so often that I can talk to people about specific streets in towns and cities with the offhand candour of a local. And when I factor in the map of Paris and the streets I know there, the streets of my flâneurial experience compose themselves into a map of my cognitive life—a vast city that is ‘Australia’, one in which the actual cities are reduced to suburbs, the towns to neighbourhoods, and the whole continental ‘city’ is linked cheek by jowl to Paris.

One thing I love about Parisian street names is the honour that is done to great people. Le Cépage Montmartrois, for instance, is located in the rue Caulaincourt. M. de Caulaincourt, the duc de Vincence, was a diplomat to Russia during the First Empire. He has a very small cameo in War and Peace. The street bearing his name intersects with the rue Lamarck, whose namesake my high school biology teacher taught me had come up with a discredited theory of evolution in advance of Darwin. At the corner of the cemetery, just before the viaduct, it also intersects with the rue Joseph de Maistre, the arch-conservative philosopher who Baudelaire claimed had taught him—along with Edgar Allan Poe—how to think.

It is often the case, as that last example indicates, that the French give the full name of the honoured person when consecrating a street to him or her. And they are not ashamed to dignify their streets with the names of foreign statespeople:—think of the avenue Georges V, the avenue du Président Wilson, etc. Anyone who has done anything great in the world earns a place in the French patrimony, and if you are a foreigner who has done a specific service to France, you are doubly honoured with a street name. They are a very generous people in that regard.

We don’t name streets after courageous foreigners in Australia, and we are even very niggardly in naming streets after the local heroes we do dignify with that honour. Thus, in this country, you find a lot of surnamed streets that are meaningless to the locals, and even in Melbourne, it is forgotten who Nicholson, Napier, or Learmonth were, even though just about every suburb has its Nicholson Street, its Napier Street, or its Learmonth Street.

If you could move to another city or country tomorrow (with all expenses covered and financial security guaranteed), where would you go if you had to rely solely on your first instinct?

My first instinct is always to return to Paris, to resume my life of oisiveté—of what I call ‘productive indolence’—in the first city of flânerie. I still crave the churning Spectacle of cosmopolitan novelty; I still crave a permanent, floating world of Truth and Beauty such as a writer can only consistently discover with the turning of random streetcorners in Paris.

It’s been sixteen years since that summer and I’m now entering my middle age. The world is a great deal more unsettled than it was then. We are entering an era of volatility that I call, in my flâneurial philosophy, ‘the Noir Place’—conditions of radical ambiguity such as the French knew during the Occupation, the period they call ‘les années noires’—the ‘dark years’, and from which experience of totalizing bleakness and blackness the term and concept of ‘film noir’ originated.

In the years since I was actually in Paris, my knowledge of the French language, literature and culture has only deepened, and I’m gratified that my vlog, The Melbourne Flâneur, is progressively becoming, year after year, one of the most consulted resources on French literature and the culture of flânerie in the English-speaking world. I’m humbled that people in the U.S., England, and Canada—as well as in this country—are looking to the southern-most corner of the globe where Melbourne lies for guidance on Parisian flânerie and to un petit écrivain australien as a reliable authority on the sources in French literature that inform it.

I recently wrote a post on The Melbourne Flâneur called “The Frenchness of Australian life” in which I expressed some of my sense, at mid-life, of coming to terms with the fact that I will probably never see Paris again, and that as I walk the streets of the cities and towns in this country, I carry a virtual Paris, and the chalice of French culture, within me, through and above the Aussie throng. I impose a fundamentally French—a fundamentally Parisian—vision on the streets that I walk.

Hemingway rightly says that Paris is a moveable feast, and that if you are lucky enough to have been there as a young man, then you carry the city with you for the rest of your life. Returned to Australia, and having slowly integrated the lessons of my Parisian experiment in flânerie into an æsthetic philosophy of living that allows me to imaginatively transform the cities, the towns, the country of my actuality into the Paris I am exiled from, to find poetry in the prosaic banality of Australian life, I begin to understand at mid-life that my destiny is perhaps to be the first ‘Franco-Australian writer’.

At the moment, when I share prose poems from The Spleen of Melbourne or the nouvelles démeublées noires from The Melbourne Flâneur with my fellow countrymen, they regard this ‘Parisian vision’ of contemporary Aussie life in Melbourne as some form of ‘surrealism’: they recognize the photographic precision of the places and the people in my words, but the application of a French literary style makes the places and the people ‘new’ to them. Suddenly the banal, prosaic, genteelly shabby local Melbourne scene becomes sophisticated, exotic, European—‘Parisian’, in a word.

Rather like Henry James—himself un grand flâneur—I wonder if my destiny as an homme littéraire is not to effect—as he did from an American angle and perspective—an Australian reconciliation with Continental Europe in my writing, to shift literary English out of the dead grasp of America and down into this hemisphere, to renovate—to ‘renouvelate’—the entire English language by finally reconciling it with French.

There is something pioneering in the character of what I am doing which I have only discovered in the years since Paris: As a literary bridgehead to our collective future as a networkcentric superorganism with a global consciousness, I am seeking the ‘New Life’ for myself and hope to find it in this young country yet ancient landscape of the ‘New World’. A friend of mine in Bellingen told me recently that Hegel says in one of his lectures that behind the rising primacy of America in the early Modernity of the nineteenth century lies the even more distant silhouette of Australia looming up on the historical horizon. Perhaps it is in my destiny as an antipodean flâneur to bridge the Anglosphere and the Francosphere, the New World and the Old in a ‘nouvelle écriture’ that today reads as postmodern and surreal but may one day strikes the eyes and ears of the coming culture as ‘classical’.

(…All that said, in this Jamesian Austral-European literary reconcilation, Italy is also a country that calls to me very deeply—particularly Venice, Florence, and Naples.)

Is there anything else you’d like to share—a poem, a book, or any other thoughts?

It’s perhaps worth sharing my other social media accounts. I have a small presence on X @TheMelbFlaneur, but the place to really interact with me is on AirChat. I see great flâneurial potential in AirChat as a social medium and I’m an active presence there. I’m very open to engaging with people who reach out to me directly for intelligent, good-faith conversations, and to participate in collective sensemaking activities scoping out potential solutions to our common existential problems, so I invite people to chat with me directly on AirChat @themelbflaneur.

And, of course, the very best place to discover more of my work, my philosophy, my books and what I do is on my website:—deankyte.com. You can subscribe to follow The Melbourne Flâneur vlog there, and I try to regularly post substantive articles on French literature, flâneurial cinema, film noir, and other aspects of my æsthetic philosophy of flânerie.

Thank you, Dean!

Thank you for reading. As always, I welcome your stories, notes, and questions.

Onwards,

Patricia Hurducaș